Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov five-day tour of his four-nation expedition – covering Egypt, Ethiopia, Uganda and the Republic of the Congo – promptly reminded the world that the regime he represents simply cannot tell the truth. Throughout his visit, none of the African political leaders or civil servants he came face to face with even attempted to challenge Lavrov’s lies. Sadly, Africa’s seemingly enthusiastic acceptance of Russia’s “alternative truths” during this visit was not in any way surprising.

Africa became one of the main targets of Russia’s post-Cold War offensive on the truth. Between 2019 and 2022, for example, Twitter and Facebook removed Russian disinformation networks that targeted Madagascar, the Central African Republic (CAR), Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Sudan, Libya, South Africa, Nigeria, the Gambia and Zimbabwe.

Since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, Russian efforts to gain favour in Africa through false narratives went on overdrive.

In March, for example, a photograph supposedly showing a young Putin training Mozambican freedom fighters in a Tanzanian military camp in 1973 conveniently emerged on African social media and generated undeserved praise and excitement. The image was also posted on Twitter by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s son. Of course, the photo is not really from the 1970s, and the man purported to be Putin is not the Russian leader.

According to Dmitry Gorenburg, an associate at the Harvard University Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Russia has established 10 main narratives that inform its strategic messaging around the world. And for a multitude of historical and cultural reasons these narratives seem to resonate especially well in Africa.

Among these, portraying Russia as “a bastion of traditional values”, in contrast to a “decadent” West, for example, appeals to conservative and homophobic segments of African society that regard sexual liberties promoted and protected by Western nations as “immoral”.

Russia’s frequent use of “whataboutism”, as explained by Gorenburg, to deflect attention from its war crimes in Ukraine and beyond also play well with audiences in Africa. This is because an overwhelming number of Africans hold the West, and only the West, responsible for the wars, conflicts and instability devastating the Global South. Many Africans, for example, view the US-led invasion of Iraq, which reminds them of similar assaults by the West on their nations as a crime and welcome what they see as Russian efforts to prevent Western whitewashing and counter Western hypocrisy.

Another messaging tool Russia uses in its war of narratives against the West, namely calling attention to the US’s history of intervening in the domestic affairs of sovereign states, also resonates well with Africans who are still suffering the results of Washington-instigated or supported coups across the continent, or mourning the US-assisted assassinations of their independence heroes, such as the DRC’s founding Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba.

And presenting Russia as a champion of “multipolarity” in the world also sits well with Africans who had suffered massively under US dominance and are keen for their nations to have their voices finally heard in the international arena.

All in all, there are many reasons why Africans support narratives pushed by Russia that underline the West’s historic and current crimes, aggressions and missteps towards the rest of the world.

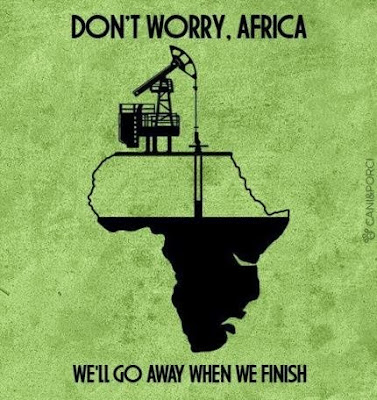

Nothing can legitimise or justify Africa’s acceptance of Russia – a colonial belligerent in its own right that has inflicted and is still inflicting incalculable pain on nations within its immediate region and beyond – as an anti-colonial saviour. Africans also need to realise how harmful their uncritical acceptance of Russia as a benevolent force for good could be for the continent.

As it expands its economic and political influence over the continent, there is little reason to expect Russia would behave differently here than it does in its traditional zone of influence.

It is already heavily involved in domestic politics in Sudan, CAR, DRC and Mali. Russian paramilitaries, particularly from the infamous Wagner Group, are fighting in several African conflicts. Strengthening ties with Russia, at a time when it is clearly in need of new “friends” to exploit to feed its war effort, would not be good news for Africa.

All this, of course, is not to say only Russian propaganda poses a threat to Africa. Africans have every reason and right to be suspicious of the narratives pushed by the West. Western propaganda and manipulation have been a major source of grievance for many African nations since independence. And the West is still working hard to spread its false or incomplete narratives on the continent to further its interests to the detriment of Africans – and the truth. For example, the state-run Voice of America (VOA), supposedly overseen by the “independent” United States Agency for Global Media, has recently been accused of blatant pro-government bias in its coverage of Ethiopia’s civil war by its own African journalists.

But this should not lead to the uncritical acceptance of Russian narratives and whitewashing of the Kremlin’s many well-documented atrocities. It is time for Africa to learn not to be manipulated by the West and Russia – for the benefit of Africans themselves, and all the other peoples of the world who have been suffering from either the West or Russia’s neo-colonial ambitions.

Taken from here

Russia (just like the West) is no true friend to Africa | Opinions | Al Jazeera